さまざまなYouTubeサムネイルテンプレート

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

教育YouTubeサムネイル

教育YouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

ファッションYouTubeサムネイル

ファッションYouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

動物のYouTubeサムネイル

動物のYouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

音楽YouTubeサムネイル

音楽YouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

フードYouTubeサムネイル

フードYouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

トラベルYouTubeサムネイル

トラベルYouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

ビジネスYouTubeサムネイル

ビジネスYouTubeサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

YouTubeの横向きのサムネイル

YouTubeの横向きのサムネイル

-

プレビューカスタマイズ

写真YouTubeサムネイル

写真YouTubeサムネイル

取消し

カスタマイズ

見逃したくない機能

豊富なテンプレート

見事な既製のテンプレートからインスピレーションを得て、YouTubeサムネイルを作成して動画を宣伝します。

豊富なリソース

高解像度のストック写真、クリップアート画像、形状、フォント、背景を使用して、サムネイルに個人的なタッチを追加します。

100以上のフォント

メッセージを伝え、サムネイルデザインを次のレベルに引き上げるために、100以上のスタイリッシュなテキストフォントが用意されています。

使いやすい

便利で使いやすい編集ツールを使用すると、わずかな手順でプロのようなYouTubeサムネイルをカスタマイズできます。

3つのステップでYouTubeサムネイルを作成する方法

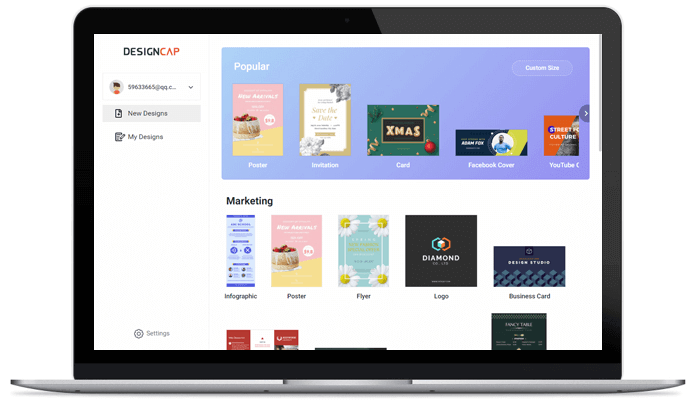

1. テンプレートの選択

テンプレートを選択してくださいYouTubeサムネイルテンプレートから選択して、デザインを開始します。

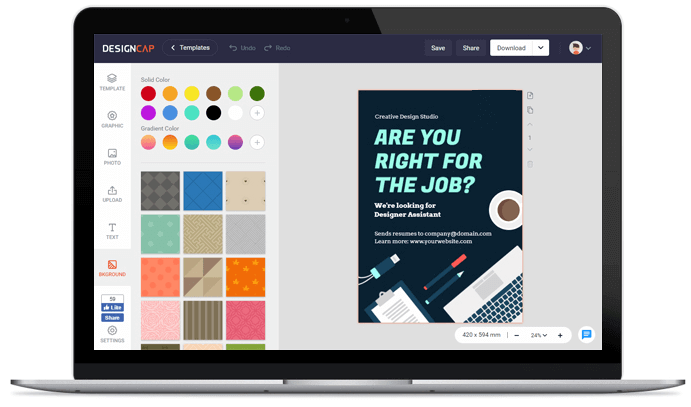

2. カスタマイズ

カスタマイズシンプルでありながら強力な編集ツールを使用して、YouTubeサムネイルをカスタマイズします。

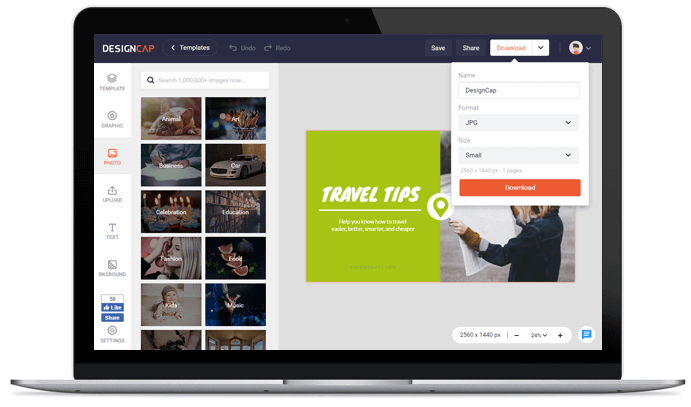

3. エクスポート

書き出すYouTubeサムネイルデザインをコンピューターに保存し、アップロードしてYouTubeビデオを要約します。

ユーザーの評価

ポスターが簡単に作成出来るポスターメーカー。何が良いって、 時間やお金、HDDのスペースを節約出来る。

といったイベントなどの広告素材を作りたいけど、プロのデザイナーにお願いする費用が無い……という場合や、スピード優先で自分でデザインしたい! といった方に最適なwebサービスです。

テンプレートを利用すれば、広告、販売、結婚式、イベント、ホリデーなどのあらゆる目的のポスターを簡単に作成することができます。